10 Million Thoughts on Banned Books Week

The most challenged books today aren't just well-established classics, but vital new work on race, gender, and sexuality

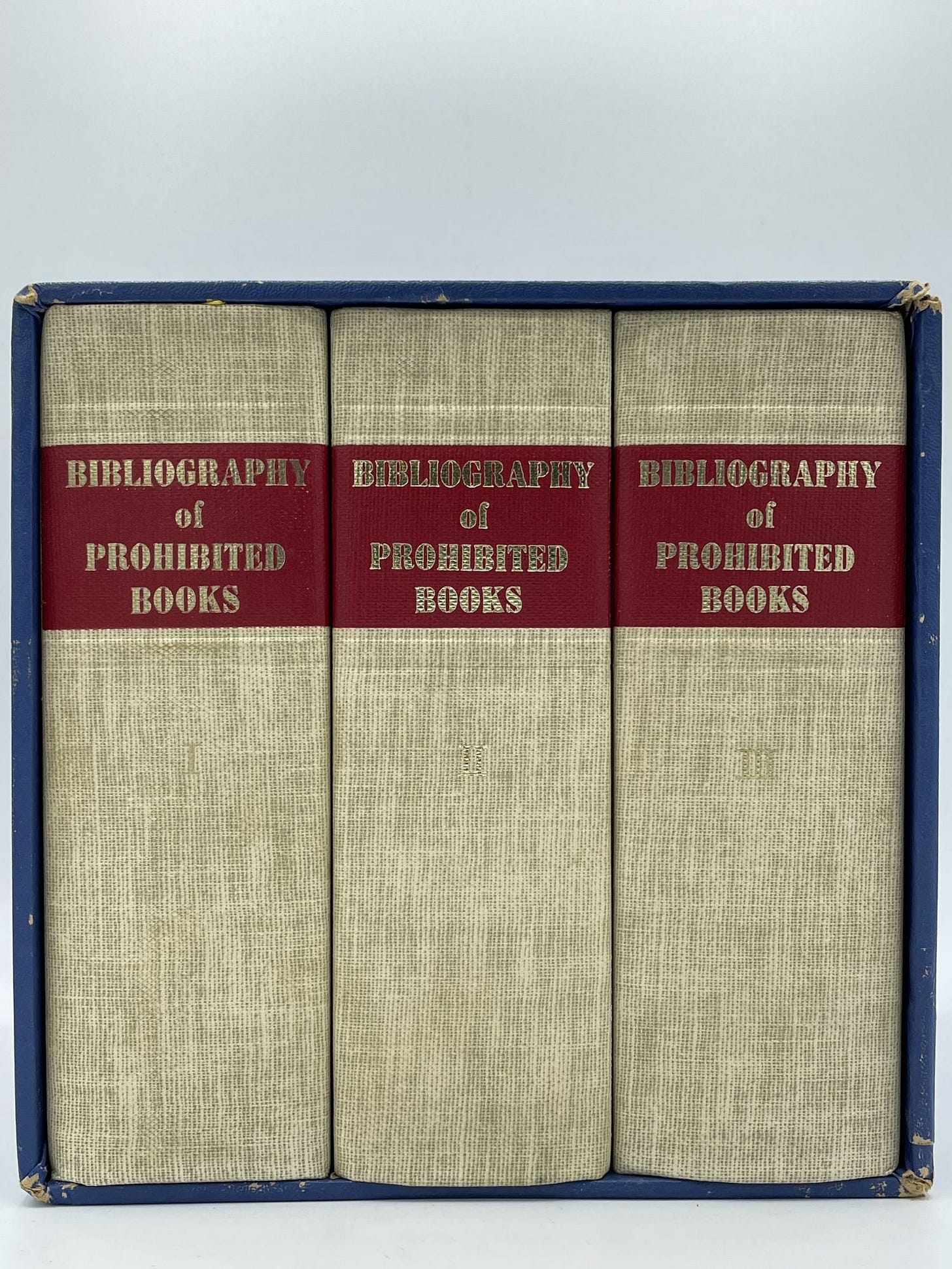

Rare Book(s) of the Week

In honor of Banned Books Week, please check out this amazing find from our rare and antiquarian collection: a 1962 edition of Pisanus Fraxi’s Bibliography of Prohibited Books. Fraxi was the pseudonym of Henry Spencer Ashbee, 19th-century England’s foremost expert on porn. If you’ve read Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith (which you really should, and we have a used copy in the store at this writing), you might recognize that Maud’s uncle is based on him. The three-volume set is in very good condition and only $50. Come in and talk to Tanner if you want to learn more, or go ahead and snag it from our website. (Update: Someone just bought it. Thank you!)

The Other 9,999,999 Thoughts

Banned Books Week started on Sunday, and I didn’t even think to post about it because 1) I was busy at the store, and 2) I still think of “Banned Books” as the ones that made the Most Challenged lists when I was young—the classics and mid-20th century titles you see on cute, anodyne Out of Print products; books in absolutely no danger of being erased from the American literary canon.

Then I looked at the American Library Association’s 2020 Most Challenged list and realized it’s not that simple.

Most of the list—George by Alex Gino; Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds; All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely; Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson; The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie; Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard; To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee; Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck; The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison; and The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas—reflects larger, ongoing right-wing assaults on marginalized people’s freedom to speak candidly and authoritatively about structural oppression.

Challenged for being “divisive,” “too sensitive,” “anti-police,” and counter to “the values of our community,” the newer books on the list reflect 21st-century educators’ attempts to create a curriculum that’s relevant to real students’ lives—one that acknowledges the existence and humanity of people who aren’t white, cishet, able-bodied, neurotypical, upper-middle-class men. Challenging those books is bad! Down with book challengers!

But then, of the three books that were on there when I was in school—To Kill a Mockingbird, Of Mice and Men, and The Bluest Eye—I can actually sympathize with arguments against two.

Let me be clear that I’m staunchly opposed to restricting children’s access to books for their own reading; leave the libraries full of ~problematic~ work for them to discover and test their own beliefs against, I say. But I’m always open to arguments that a book has outlived its pedagogical utility.

Of Mice and Men, written during the eugenics movement’s salad days, makes a caregiver killing a disabled man into a heroic, if tragic, act. And it does that after turning that man into a killer himself, thanks to some combination of neurodivergent sensory issues and sexual desire that the reader is meant to find unseemly in an “innocent” and “childlike” disabled adult. (Sorry to spoil an 84-year-old novel.) Not great!

“The inevitable question in all classroom readings of Of Mice and Men is to what extent George’s action in killing Lennie at the end of the book can be justified,” writes Clare Lawrence in “Is Lennie a monster? A reconsideration of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men in a 21st century inclusive classroom context.” Lawrence tries valiantly to establish parameters for a productive, non-harmful discussion of Of Mice and Men, but in the end, you’re still left with an English teacher asking children to discuss whether certain marginalized people might be better off dead—a question with grave real-world implications.

Are the literary and pedagogical qualities of Steinbeck’s text really so uniquely valuable that they’re worth encouraging teens and tweens to treat the worth of disabled lives as a thought experiment? Especially when any given classroom probably contains some with learning differences, autism spectrum disorder, and/or disabled loved ones?

To Kill a Mockingbird, similarly, is challenged from the left these days by those who see its white savior narrative as shallow, outdated, and racist. 2015’s Go Set a Watchman, which depicts said white savior as a crochety old bigot, suggests that even Harper Lee agreed with that basic critique. After Watchman, many white readers’ fond memories of Atticus Finch were shattered, but, as Adam Gopnik writes in The New Yorker: “[T]he idea that Atticus, in this book, ‘becomes’ the bigot he was not in ‘Mockingbird’ entirely misses Harper Lee’s point—that this is exactly the kind of bigot that Atticus has been all along.”

Black readers didn’t need that explained to them. In this panel review of Watchman, Medill professor Steven W. Thrasher writes:

Atticus Finch did not fall off any pedestal for me, though. While he has long operated in the American imagination as a kind of moral compass against racism, the idea that a white southerner of that era could be “gentleman” enough to be above racism was always ludicrous to me. I watched the 1962 film the night before Watchman dropped, and Gregory Peck’s Finch struck me as corny in a woefully naive plot. The story was primarily concerned with the preservation of and disruption to white innocence, illustrated by children who seemed to have been brought straight from the set of the Little Rascals. The fate of black people in general (and accused rapist Tom Robinson specifically) was secondary to whiteness and how white innocence was tested.

White people have loved To Kill a Mockingbird for generations in large part because it makes racism into a clear villain, easily slain by good intentions. It centers our experiences and feelings while asking very little of us in terms of empathy for the victims of white supremacy. That doesn’t mean it’s a bad book—it’s manifestly not on a number of levels, and my point isn’t to shame anyone for loving it, or even teaching it. But it’s not the right launchpad for a meaningful classroom discussion of race in 2021, and it was never actually the best we could do. I would not be sad to see it replaced on high school and middle school reading lists.

But wait, I get worse!

I am fully in favor of “canceling” some authors, by which I mean “encouraging people to teach other, better authors instead.” Take The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian. Pro: It’s an award-winning young adult novel written by an indigenous author—and indigenous voices are too often left out completely, even when white educators take a conscious stab at diversifying their reading lists. Con: In 2018, ten women talked to NPR about Sherman Alexie’s inappropriate sexual behavior with them.

If Alexie were the only indigenous author exploring teen territory, I’d maybe entertain an argument for separating the art from the artist. Fortunately, he’s not. Youth literature scholar Celeste Trimble suggests Louise Erdrich’s The Round House (2012), Tommy Orange’s There There (2019), and Brandon Hobson’s Where the Dead Sit Talking (2018) as strong (and more recent) examples of indigenous literature with teen protagonists. None of those novels is marketed as “young adult fiction,” but work by Cynthia Leitich Smith, Cherie Dimaline, and Eric Gansworth is. There are excellent options now that weren’t there even twelve or fifteen years ago. Relegate Alexie to the library, I say, and select a worthier author’s book for class discussion. *bangs gavel*

Unfortunately, I’m not in charge of anyone’s curriculum decisions. Fortunately, neither are most of the people challenging The Hate U Give because they’re made uneasy by perceived threats to white supremacy. But the fact that book challenges come from both the right and left doesn’t mean it’s a wash. There’s a crucial difference between censoring any work that challenges the status quo and de-prioritizing old favorites so that more voices can be heard in full.

In an age of rampant disinformation, it may no longer be entirely true that the best remedy for bad speech is more speech. But the best remedy for bad books—and just about anything else what ails ya—will always be more books.

Spooky New Books In Store!

As always, you can order any new books you like from us via Bookshop, Libro, or MyMustReads. But during Spooky Season, you’ll also find new copies of horror and thrillers by the likes of Carmen Maria Machado, Victor LaValle, Neil Gaiman, Stephen King, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Shirley Jackson, Mary Shelley, and more.

All through October, we’ll also be displaying spooky titles from our used stock—everything from Mary Roach’s Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers to Ruth Franklin’s biography of Jackson, Kelly Thompson’s Storykiller, plus some random horror, true crime, thrillers, and the just plain weird shit you love us for. Come in and see for yourself.

Until next time,

Kate

Love these thoughtful essays showing up in my inbox. Going to buy some books here soon to say thanks.