Those of you who aren’t extremely online—or extremely Twitter-online—may have missed this week’s literary kerfuffle on the subject “Is poetry powerful, or nah?”

First, Barren magazine poetry editor Danielle Rose tweeted,

I wish poets understood that the general population has no interest in what we do, so when we speak we are speaking only to each other. The delusion that poetry is something powerful is a straight line to all kinds of toxic positivities that are really just us lying to ourselves.

“I don’t find this defeatist,” Rose added, but many commenters did. The Barren editorial board quickly moved to clarify that they disagreed with the original tweet, and Rose would be leaving her volunteer position. At which point it turned into a whole “cancel culture” thing, which, ugggggggh. Any discussion involving those words in 2021 inevitably degrades into a bunch of mostly disingenuous yelling, so we will leave that aside.

I want to go back to the original point. Is poetry “something powerful,” or is that a “delusion”?

First, we need to ask some follow-up questions. Like, “What do you mean by ‘powerful’?” And “Are ‘powerful’ and ‘important’ the same thing?”

And then there’s the question we must always ask when someone makes a declarative statement about The Way a Thing Really Is: “To/for whom?”

I am not actually asking these questions of Danielle Rose—though she’s hit on some of them in her follow-up tweets—but of the universe, and myself, and perhaps you, the reader, if you would like to comment.

Here’s what I think.

Poetry is categorically not “powerful” by the usual definitions of “power” in a capitalist society. Which is to say, it generally doesn’t sell well unless the poet is already very famous (ideally for something that is not poetry). Most books don’t sell very well, most writers don’t make very much money, and among writers, poets tend to make the least.

And yet, here we are, selling books. Here writers are, writing them. Here poets are, poeming away.

Because we love it.

People love books because of how they make us feel—or made us feel, back when we first became readers. Transported. Connected. Seen. Changed. Writers, publishers, and booksellers are people who have been so overwhelmed by that experience, we felt compelled to create it for others. Surely, this is a kind of power?

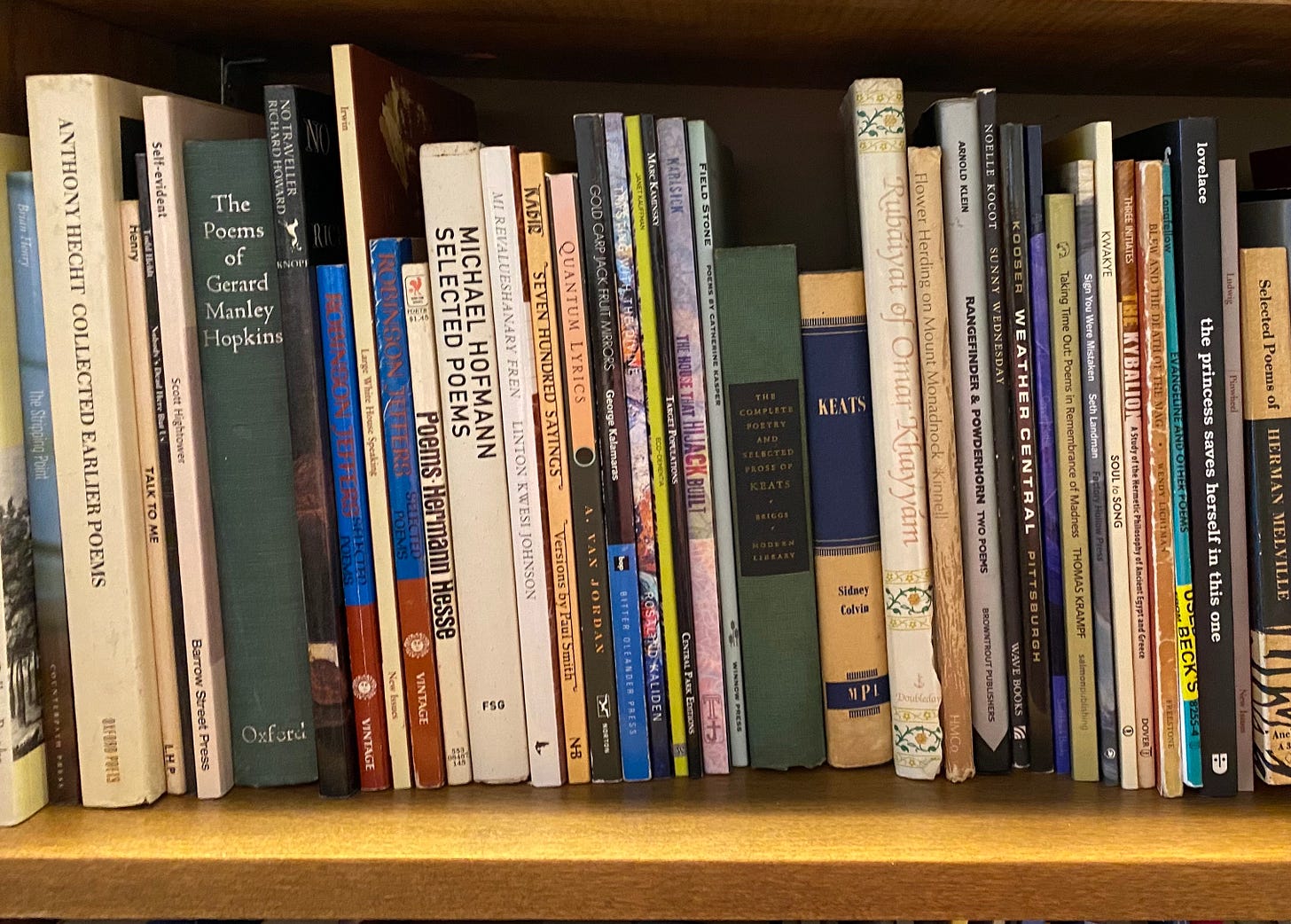

Poetry, in particular, also holds a different kind of power—the power to frighten and intimidate. So many people who read prose with confidence have been convinced they “don’t get” an entire genre, usually because of the poetry they were forced to read in school. Then, once you’re out of school, where do you find new poetry? Loads of it is published every year, but almost none of it with a marketing budget. And because almost none of it sells terribly well, a bookseller who doesn’t keep up with new poetry for their own reasons can’t even offer a generic, “Well, this one’s very popular!” about anything except… the titles we all had to read in school.

(I should note that we do sell a fair bit of poetry at Uncharted, all things considered, and we have a wonderful, eclectic selection; on this point, I’m speaking more from the perspective of someone who used to work in small press than someone who currently sells books.)

This, I think, is what Rose was getting at. She’s not wrong that poets are primarily writing to each other, because people who write poetry are the ones most motivated to seek out other poets via readings, small presses, and lengthy used-bookstore browses. Again, in my experience, this is true of all writers. We like to believe we’re writing for the general public—or at least a hypothetical ideal reader who, hypothetically and ideally, will have tens of thousands of similar friends who would also like our books. But unless you’re very famous, your literary events will be populated by two groups of people: 1) your family, and 2) other writers, who showed up to your thing in hopes that someone will show up to their next one.

This is not a complaint! It’s how writing communities develop, and the one we have in Chicago is extraordinary. A writing community is, in itself, a very powerful thing—for certain values of “powerful.”

Last weekend, one of my best friends from my MFA program, Suezette Given, was in town to receive an award from the American Writers Museum. Suezette hasn’t yet published a book herself. She carved out time to do her master’s in poetry while working full-time as a high school English teacher and raising two spectacular children. But one of her former students, Jenny Xie, has published some books, and won some awards, and been nominated for some others. Her first full-length collection, Eye Level, won the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets. (Her chapbook Nowhere to Arrive is also available through our Bookshop.org portal.)

The museum asked Xie to present its annual Inspiration Award to someone who had an impact on her development as a poet. She chose Suezette.

I cried real tears when I heard. If you are of a certain age (mine), you will recall the film Mr. Holland’s Opus, about a musician who becomes a high school teacher and spends a few decades worrying that he’s wasting his artistic life—all the while failing to appreciate the way he’s shaping other artistic lives. I have no idea if the movie holds up and don’t want to know if it doesn’t. The point is, I sobbed at the end of that, too, and I’ve been describing this to everyone as Suzi’s Mr. Holland moment. (Except she’s still got many years ahead of her as a teacher and a poet, so this is simply a career highlight, as opposed to the pinnacle.)

Anyway, all of that is, I imagine, what Rose’s detractors were getting at. Poetry has that kind of power in abundance. The power to connect a teacher and a student for decades after graduation. The power to forge new neural and career pathways in a young artist. The power to keep creating more poets in every generation—no matter how little the general public currently values their work (for certain values of “values”)—even if they mostly end up talking to each other. Because what’s better than talking to other people who get it?

The love of the thing. That’s power.

Are We Your Favorite?

Here’s a gentle reminder that if you set Uncharted as your favorite store at Bookshop.org, we get the full profit from your order. Otherwise, the profit goes into a pool for many indie booksellers, which is obviously also a lovely thing! We’re not going to tell you what to do, apart from telling you to please remember that Bookshop exists when you’re tempted to order from the other place.

See you next week!