First, The Business Section

We will be closed on Halloween, Sunday, October 31!

But we’re very much open today, Saturday, 11-7. I will be dressed as Shirley Jackson and kicking myself for getting a haircut recently, because I can’t perfectly achieve this look anymore. (It’s still close, but there are too many layers on top to get the full Shirley poof. Tragedy.)

From Our Rare Collection: Edward Gorey

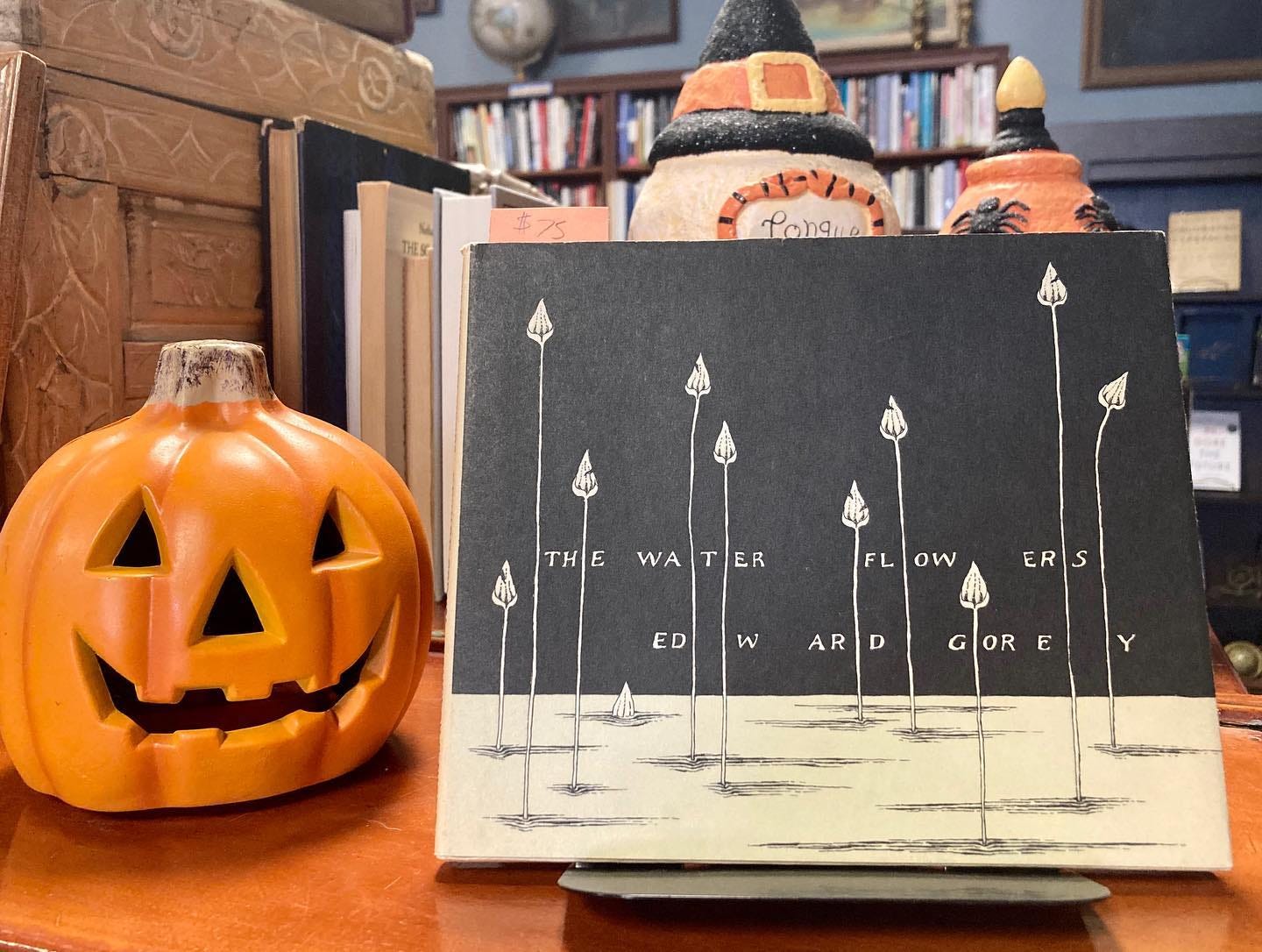

Happy Halloween! Can I interest you in an Edward Gorey first edition? We have several in very good condition!

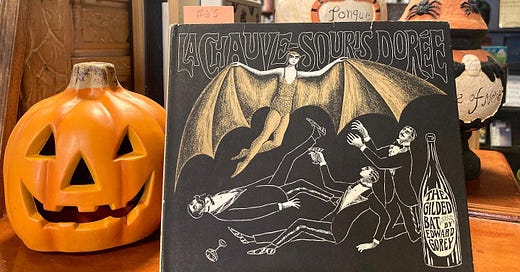

How about The Gilded Bat, for $85?

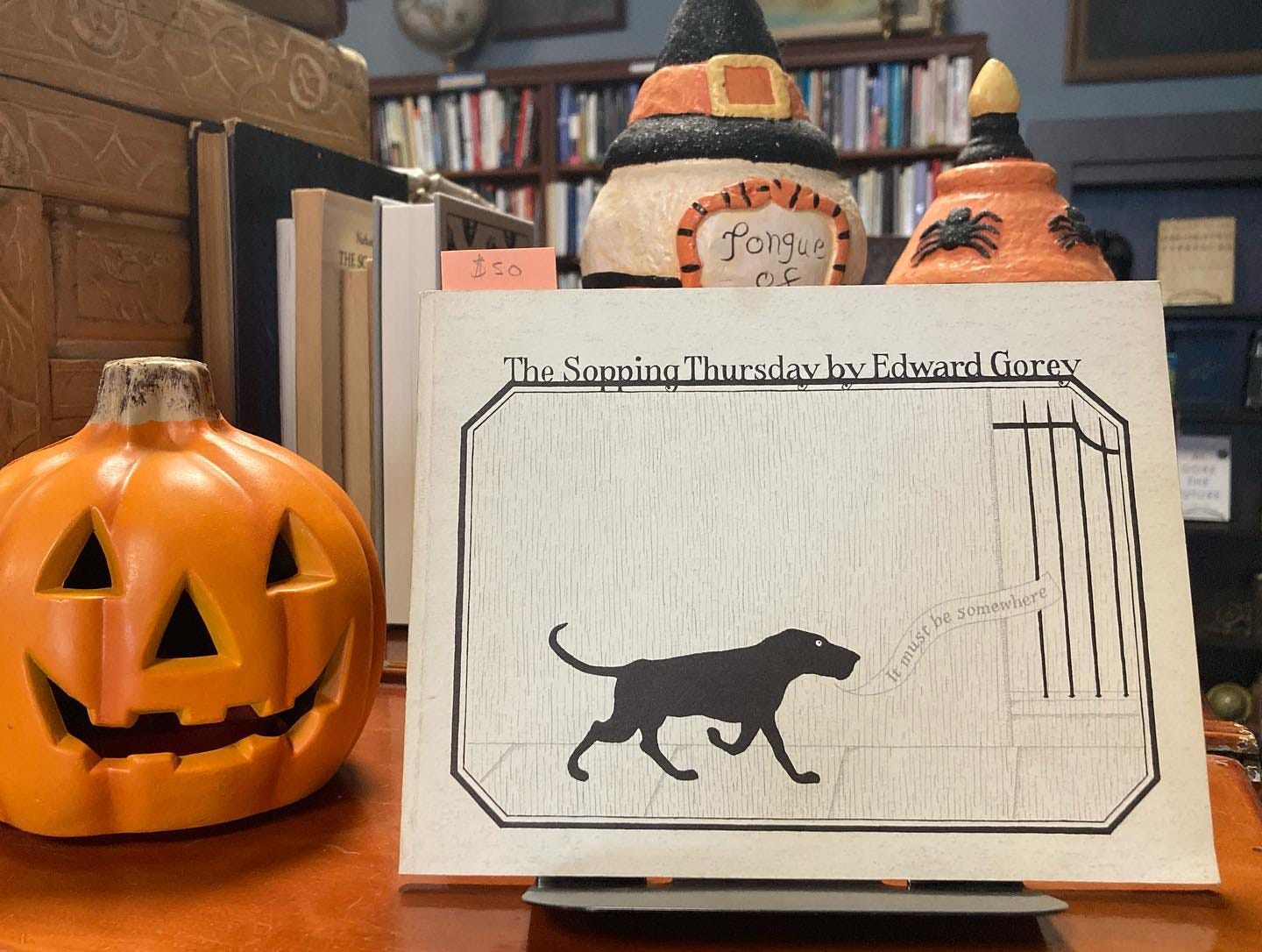

Ramona fans will surely be interested in her alter ego on the cover of The Sopping Thursday ($50) here.

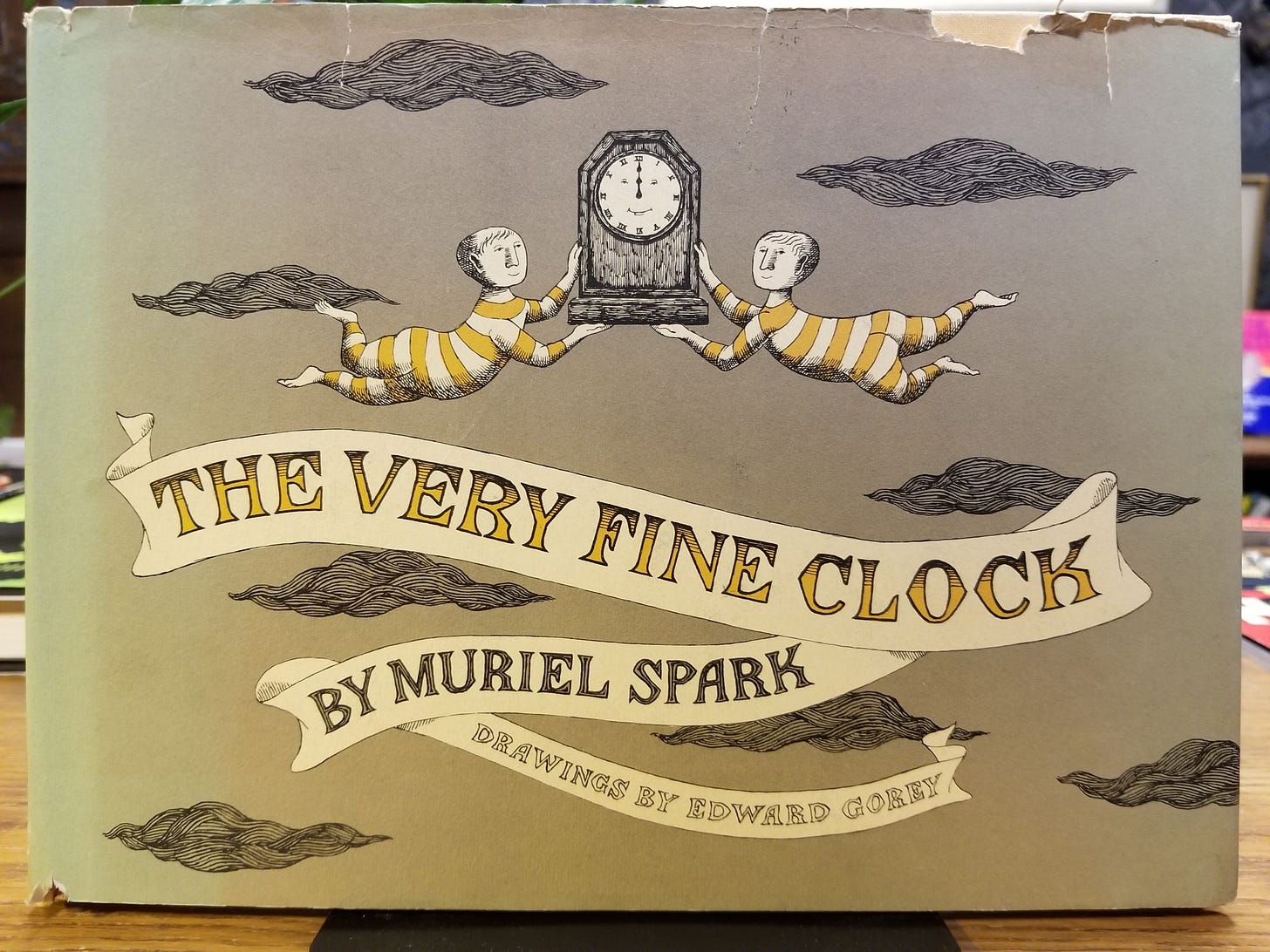

We also have several books written by other people and illustrated by Edward Gorey. Other famous people even! How about Muriel Spark? ($150)

Or perhaps what you really need is a SIGNED first edition of this amazing pop-up book,The Dwindling Party, for only $500? (Click through to see images of the interior.)

Our full Gorey collection has titles starting at $15. Please go clean us out!

The Part Where I Remind You Where to Buy Stuff from Us Online:

Rare and Antiquarian: The store website!

New books: Bookshop!

Audiobooks: Libro.fm or MyMustReads!

Ebooks: MyMustReads!

And Now, the Section Where I Write Too Many Words About Books

Previously: The Books You Broke Up With, Part One.

Lionel Shriver, We Need To Talk About Kevin (2003)

A customer recently asked me if I thought a Lionel Shriver novel was any good, and I told him I truly had no idea—in recent years, she’s become (or more clearly revealed herself to be) someone I can’t respect, so I haven’t read anything by her in ages. A writer who characterizes social justice-minded criticism as “name calling, silencing, vengefulness, and predation” (and her own refusal to engage with it in good faith as caring “about excellence more than virtue,” lol) is not someone I trust to think deeply and clearly about human relationships, the animating force of fiction.

But I loved her breakout novel, We Need to Talk About Kevin, which looks deeply at a woman’s ambivalence about motherhood in the most taboo of contexts: after she’s already had children. One of those kids has committed an unspeakable crime, and his mother makes an unflinching examination of how he got there. Was Kevin born a sociopath? Or did her inability to love him fully as he was—a colicky baby, a cold and angry child, a dangerous teen—turn him into a monster?

The answer, as you might suspect, seems to be “both.” Compared to her younger, easier, happier child, it’s clear that Kevin came out of the womb different, but it’s also clear that his mother, Eva, could never completely conceal her distaste for him. For Kevin, every developmental milestone comes with frustration, and Eva increasingly believes her son is deliberately failing to progress—faking not being able to speak; stubbornly refusing to use the toilet; screeching “Nyeh-nyeh!” endlessly, well beyond the age at which most children have moved on. (We are meant to understand that the character is of above-average intelligence but, at best, emotionally immature.)

Eva’s husband, Franklin, thinks Kevin is just a normal, kinda bratty little boy, and the gulf between the couple grows as Eva sees premeditated malice in her son’s every action. Which one of them is right? Who understands Kevin better? And how is a child’s emotional development affected by both a chronically suspicious mother and a father who keeps enough distance to ignore obvious patterns?

These are fascinating questions, and Shriver absolutely goes there. Eva is right, generally speaking; we know from the start that Kevin grows up to murder several people, two days before his sixteenth birthday. And Eva, who never wanted children, is the one expected to care for and think about Kevin’s needs 24/7, while Franklin is both free and content to regard him as more symbol than person: My Son, who made me A Father. We sympathize with Eva’s coldness toward Kevin in large part because Franklin treats her like she’s delusional while refusing to look more closely at his child’s behavior.

But also, she’s kind of terrible!

Shriver’s willingness to let every character be unlikable—indeed, culpable—in some measure is a major strength of the novel. There are no easy conclusions. And like so many writers who are popular, lauded, and problematic all at the same time, she makes some impeccable observations about human behavior. She limns specific strains of resentment, narcissism, competition, cruelty, and self-justification with the very best of them.

But then she starts a sentence with, “I hope this doesn’t sound racist—these days, I never know what will give offense…” And even though that’s in Eva’s mouth, and Eva is kind of terrible, it’s clear you’re meant to nod along with the observation that follows—which is, in fact, racist.

I didn’t remember that line in particular, but when I started to write this newsletter, I picked up a copy of We Need to Talk About Kevin and skimmed for indications that Lionel Shriver would eventually become… whatever an enfant terrible is when the enfant is well into middle age. It took about 30 seconds to start finding red flags, which was a bummer but no surprise. A person who would wear a cheap sombrero while declaring, “I am hopeful that the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’ is a passing fad” usually drops some clues before she fully commits.

In fact, Shriver had already lost me years before that, because of the way she wrote about her late brother. When he died in his fifties, Shriver’s brother was very fat which, in a Daily Mail piece I won’t link to, the author fixates on as the emblem of everything that went wrong in his life. A moped accident, a severe beating by “thugs,” a period of alcoholism, a failed business, and two “imploded” marriages are all dispensed with quickly, but his fatness—which literally causes her to look upon him in “horror”—haunts her so much, she wrote an entire novel about it.

Lest you think a novel might contain a more nuanced view of fatness than a Daily Mail article, even an NPR review that claims the book “champions compassion for the corpulent” goes on to say in the very next sentence that “its not-so-subtle bias toward the slim and disciplined is evident” (and quotes some cheap, fatphobic wordplay to make the point). So I wasn’t all that surprised when, in 2016, Shriver gave the sombrero speech, published a novel in which a white man’s Black trophy wife develops early-onset dementia, and told an interviewer she conceived of the woman’s increased care needs as punishment for the man’s vanity.

By the middle of the second decade of the 21st friggin’ century, the internet was full of grade schoolers who could explain why it’s not okay to use characters of color as props to advance a white character’s story or, for that matter, disability as any kind of punishment. But people only criticized that novel’s racism, Shriver said, “because it doesn’t toe a strict Democratic Party line.” And here we arrive at the problem with so many authors who are outstanding observers of human behavior, right up until they’re asked to consider how their own behavior harms other people. Brilliant thinkers can become mind-bogglingly lazy ones when held to account for the pain they cause through their own failures of imagination.

Treating marginalized characters as exotic, repulsive, or otherwise not fully human—not because the story somehow demands it but because the author obviously hasn’t reckoned with their own biases—is bad writing, over and above the fact that it makes real life worse for real people. Dismissing such criticism as hypersensitivity, or worse, an insincere attempt to score political points, is as shallow as it is solipsistic. And the problem with being a sometimes brilliant author is that we all know you’re not a shallow thinker.

You could do better. You just didn’t.

Which brings us to:

Philip Roth, The Human Stain (2000)

I once tried to explain to a friend why I was reading The Human Stain, on purpose, despite the racism and misogyny threaded through it like mold. The protagonist, Coleman Silk, is a Black man who has passed as white throughout his career as a college professor. When he inquires about the whereabouts of two students who never show up for class, calling them “spooks”—as in ghosts, invisible people—he sets off a firestorm that leads to his indignant resignation and subsequent downfall. The missing students, it turns out, are Black, and even though he had no idea, Coleman’s word choice is taken as a racist slur.

This is a novel about political correctness run amok, the favorite subject of people who fancy themselves open-minded even after time, money and excessive praise have corroded them into intellectual versions of your Fox News-obsessed uncle. It’s also a novel whose most noteworthy female characters are 1) a 34-year-old woman who wants to keep her relationship with 65-year-old Coleman strictly sexual, and 2) a cartoonish feminist professor whose unhinged vendetta against Coleman boils down to, you guessed it, her overwhelming lust for him. But it’s also also a novel about aging, self-loathing, twentieth-century masculinity, and other subjects Roth did better than most. So what I said to my friend was: When he’s right, he’s both so right and so confident, it’s a marvel to read.

You’ve heard Sarah Hagi’s quip, “Lord, give me the confidence of a mediocre white man”? Well, the confidence of a white man who (sometimes) has the goods to back it up is a thing to behold. It’s the literary “voice” equivalent of a news announcer’s stentorian sound, at once authoritative and reassuring. “I am going to teach you something you would never have figured out on your own,” that voice says. “But I respect you enough not to over-explain or burden the insight with a list of caveats. You’re an intelligent person; surely, you’ll get it right away and agree.”

As a reader, I eat that shit up, which means that as a writer, I always want to know how to do it better—how to say a thing you believe to be true about the world and leave it alone, confident that it’s both correct and well articulated. That’s why I was reading The Human Stain, and why I’d still recommend We Need to Talk About Kevin, which is full of similar energy. The problem with Roth and Shriver and so many others is that when they’re not right—when they’re writing lazily, from a place of defensive exasperation—they do it with every bit as much confidence. “This is the way the world really is,” their dauntless voices declare, while your brain whispers back, “…it’s not, though?”

That’s the real issue with cultural appropriation, which Lionel Shriver is surely smart enough to understand. If you’re going to write about characters very different from yourself, you have a responsibility to do so without leaning on stereotypes and self-serving fantasies. No one is telling white authors not to write characters of color, men not to write women, cis people not to write trans characters, etc. They’re telling you not to do it badly, in a way that hurts people and reflects poorly on both your empathy and your research skills. There’s an obvious difference between making a good-faith attempt to bring realistic characters to life and using marginalized characters as self-exonerating ventriloquists’ dummies.

So I can’t tell you, dear reader, if you will enjoy a given Lionel Shriver or Philip Roth novel. I can only tell you I apparently have a lot to say about a couple of them, and maybe that alone means they were worth reading. I can also remind you there’s no guilt about supporting a problematic author if you buy the book used. *jazz hands*

Please Bring Us More Books I Don’t Have to Apologize For

We are always looking for the following genres, especially if it’s newer work by authors who aren’t the same old, same old:

Sci Fi

Fantasy

Literary Fiction

Philosophy

Poetry

Comics

Mystery/Thriller/Suspense (see exceptions in next section)

Small Press Titles

We are pretty much never looking for:

Textbooks

Heavily marked books

Older self-help or travel guides

Test prep books

Programming books

Older Chick Lit

Airport Novels—e.g., John Grisham, Dan Brown, any mass market paperback thrillers by super-commercial authors. (We’d be happy to take these if they sold, but that’s just not what people come to Uncharted for.)

Okay, thanks everybody, good talk.

Until next time,

Kate